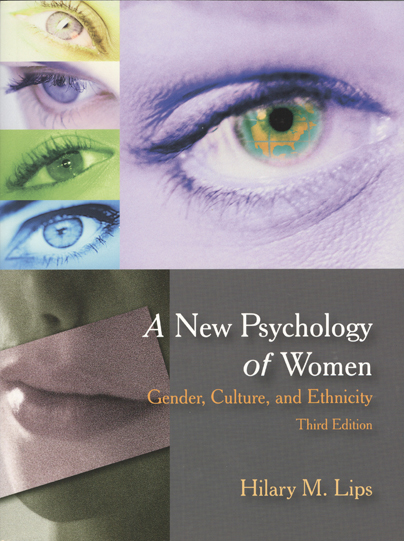

A

New Psychology of Women

Gender, Culture and Ethnicity ~ Third Edition |

Feminist

Studies Display

Art: U. of Canterbury

|

|

Art: U. of Canterbury

|

"Peering into the Kaleidoscope"

Cross-cultural

Perspectives in the Psychology of Women & Gender

by

Professor Hilary M. Lips, Ph.D.

1999 Fulbright NZ-U.S. Award Recipient

at the

University of Canterbury

Copyright © 1999 H. Lips. All rights reserved

March 13th, 1999

|

Presentation

Summary:

Thank you, Dr. Jaber for your introduction. Let me begin by saying

how very pleased and honored I am to be here and to be a part of the

process of looking at the very important issues surrounding women

in education. I offer my thanks to Dorothy Meyer, who spearheaded

this visit, and to all of you for your hospitality. I'll begin my

talk today, with a brief overview of four very remarkable women.

|

Dr.

Lips Introduction by Dr. Nabila Jabber:

Feminist Studies -- University of Canterbury

|

*

Amelia Edwards

In 1873, Amelia Edwards, a redoubtable

Englishwoman, published an account of her travels through the Dolomites.

The book, Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys, documents

her journey with another woman -- on foot and on horseback -- through

terrain that was rough and uninviting to travelers, particularly women

travelers. At a time when most English gentlewomen led sheltered,

even uneventful lives, Amelia Edwards craved and found adventure in

her explorations of the world around her. Not content with the vision

of the world that she had inherited as a white Victorian woman of

comfortable means, she traveled the globe with her women friends to

gain and communicate new perspectives.

Ms. Edwards was an ardent advocate

of women's rights. She correctly intuited that women needed to step

out from the protective shelter of their own families -- even their

own country and culture -- to undertake their own journeys and gather

their own experiences, if they were to develop a sense of independence

and strength. Amelia Edwards followed her own advice: she forged an

exciting life as an adventurer, travel writer, and archeologist. She

journeyed to remote corners of the world, wrote well-received novels

and travel books, rose to prominence as a lecturer in Egyptology.

As one of the very few women of her times to try to gain a "global

perspective," surely she is an appropriate pioneer to place at the

beginning of this lecture.

* Bessie Coleman

In 1921, Bessie Coleman earned

her pilot's license. Born, not to privilege, but to poverty, she had

spent the early years of her life picking cotton and living in a three-room

shack in east Texas -- an unlikely start, perhaps, for the world's

first African-American female aviator. It was while she was working

as a manicurist in Chicago that she began to dream of flying. When

no one in that city would teach her to fly, she raised the money to

travel to France. There she studied at one of the best flight schools.

She became a glamorous and daring flyer, drawing large crowds when

she performed in air shows. She died tragically at the age of thirty-four

when she fell from her plane as it nosedived toward the ground. She

had been preparing for a flying exhibition in Jacksonville, Florida.

Bessie Coleman, who could barely

write, left few records of her accomplishments or of her thoughts

and feelings about her flying career. Because she was African-American,

mainstream newspapers of the day gave her exploits little coverage.

After her death, her accomplishments faded into obscurity for many

years. In 1996, she was recognized again after many years of invisibility,

and was featured on a 32-cent U.S. postage stamp. As a woman who insisted

on seeing the world from a new perspective, in defiance of the restrictions

associated with her race, class, and gender, Bessie Coleman too is

an appropriate ground-breaker to place at the opening of this talk.

*Mae Jemison

In 1992, Mae Jemison blasted off

on the space shuttle "Endeavor," becoming the first African-American

woman to travel into space. As a child growing up on the south side

of Chicago, she had watched the stars in awe, dreaming that someday

she would visit them. Her route to the stars took her through a host

of high school science projects, university training as a chemical

engineer, training in choreography and dance, a medical degree, a

stint in the Peace Corps in Thailand. Through it all, she learned

to think of her life as a journey, and not to limit herself because

of anyone else's limited imagination.

Jemison, a modern-day explorer

who now spends a good deal of her energy encouraging young women to

expand their horizons, sees the world as a small and interconnected

place. Viewed from space, the earth presents a face that inexorably

calls forth a global perspective. As one of the few women who has

seen that face, Mae Jemison too is a good model for the beginning

of this lecture.

* Rigoberta Menchú

In 1992, at the age of 33, Rigoberta

Mench£ was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, praised by the Committee

for standing "as a uniquely potent symbol of a just struggle." A Mayan

Indian of the Quich‚ people, Rigoberta grew up in Guatemala, a member

of a family in which her mother was a midwife and healer and her father

was a community leader and organizer. As a child she picked cotton

and coffee beans, and later worked as a maid in Guatemala City. Before

the age of 20, she was involved in her father's organization, the

Committee of Peasant Unity, traveling with him around the countryside

and urging Native American peoples to resist the appropriation of

their land and villages. The struggle proved to be a tragic one for

her family: her younger brother was tortured and burned alive by government

soldiers because of his political activities. In 1980, her father

and 39 others were killed when government troops attacked the Spanish

embassy which they were occupying in a peaceful protest. Three months

later her mother was kidnapped and raped, tortured and killed by soldiers.

Menchú was literally forced

into the international arena by these events. In memory of those killed

at the embassy, she formed the "31 January" organization a group of

peasants, students and workers who organized demonstrations and labor

stoppages to protest government policies. Soon she was wanted for

"subversive activities" and fled to Mexico. She told the world about

the conditions in Guatemala through her autobiography,

Rigoberta Menchú, an Indian woman in Guatemala (1983),

and joined international efforts to protest human rights abuses by

the Guatemalan government. As a woman who was forced by events to

move beyond her own culture and whose activism has encouraged many

others to look beyond their own borders, Rigoberta Menchú, too

is an appropriate symbol to place at the beginning of a talk about

multicultural perspectives on women and gender.

- What do these individuals have in common? They are women

.... They are extraordinary...

- What do they have in common with less remarkable or famous women?

- Do they share more than female biology?

- Do they share certain kinds of restrictions or expectations ....

One of the things that women may

have in common is the quality of the barriers they face. Different

groups of women may vary in the ways in which they experience and

interpret those barriers, in the strategies they adopt for overcoming

them, in how successful they are at transcending them. For instance,

the four women described here shared certain barriers, despite the

dramatic differences in their lives. All faced cultures in which men

were traditionally the leaders, the great explorers, the adventurers.

Women, with fewer resources and surrounded by an ideology that they

should be home-centered, were supposed to wait and worry while men

went out into the world. These obstacles are different in degree,

but perhaps not in kind, from those facing many women of many different

backgrounds.

- What kind of a psychology of women would address the experiences

of all these and other women?

We can look for commonalities and themes, but the differences are

also interesting.  Currently,

we look mainly at white, middle-class U.S. women and men in our courses

on the psychology of women and gender. How can we separate what goes

with being female or male from what goes with being white, middle-class,

American? We cannot. And this makes it look as though certain qualities

or behaviors that correlate with being female or male in this culture

are inevitably linked to sex or to gender. The title for this talk

was suggested by a quote from Australian literary scholar Sneja Gunew:

In trying to grasp the experiences of women from a variety of times

and places, "we should perhaps use the image of a kaleidoscope, where

each turn produces different patterns and no single element dominates"

Sneja Gunew (1991). Currently,

we look mainly at white, middle-class U.S. women and men in our courses

on the psychology of women and gender. How can we separate what goes

with being female or male from what goes with being white, middle-class,

American? We cannot. And this makes it look as though certain qualities

or behaviors that correlate with being female or male in this culture

are inevitably linked to sex or to gender. The title for this talk

was suggested by a quote from Australian literary scholar Sneja Gunew:

In trying to grasp the experiences of women from a variety of times

and places, "we should perhaps use the image of a kaleidoscope, where

each turn produces different patterns and no single element dominates"

Sneja Gunew (1991).

Let's take a look into this kaleidoscope:

Examples: Hima women being fattened up for marriage:

Among the Hima people of western

Uganda, fat is beautiful -- at least for women.  Men measure a woman's attractiveness by her obesity, and a young woman

is prepared for marriage in ways guaranteed to "fatten her up": the

least possible activity and the most possible food. By the time of

her marriage, the young woman may be so fat that she cannot walk,

only waddle. At the wedding, onlookers then will comment on how beautiful

she is, noting with approval the cracks in her skin caused by the

fatness and the difficulty with which she walks. Once married, a wife

is kept fat by consuming surplus milk from the herd -- often coerced

to do so by her husband when she has long past the point of satiation.

The wife leads a life of "leisure." She is assigned no heavy physical

work, rarely leaves home, spends her days in sexual liaisons with

a variety of men approved by her husband. These sexual relationships

cement economic ones: the obese, conspicuously consuming wife is both

a symbol and an instrument of her husband's economic prosperity (Tiffany,

1982).

Men measure a woman's attractiveness by her obesity, and a young woman

is prepared for marriage in ways guaranteed to "fatten her up": the

least possible activity and the most possible food. By the time of

her marriage, the young woman may be so fat that she cannot walk,

only waddle. At the wedding, onlookers then will comment on how beautiful

she is, noting with approval the cracks in her skin caused by the

fatness and the difficulty with which she walks. Once married, a wife

is kept fat by consuming surplus milk from the herd -- often coerced

to do so by her husband when she has long past the point of satiation.

The wife leads a life of "leisure." She is assigned no heavy physical

work, rarely leaves home, spends her days in sexual liaisons with

a variety of men approved by her husband. These sexual relationships

cement economic ones: the obese, conspicuously consuming wife is both

a symbol and an instrument of her husband's economic prosperity (Tiffany,

1982).

Chinese women having their feet bound:

In China, and in the Chinese-American community in the United States,

until the early part of this century, it was common for young girls

to have their feet tightly bound. Small feet, "golden lilies," were

considered a sign of beauty and refinement, so the purpose of binding

them at such a young age was to keep them from growing to full size.

The binding deformed the feet and kept them from developing the normal

strength and flexibility needed for walking -- making it difficult

or impossible for a woman to walk unassisted. However, these women

were not necessarily being prepared for a life of leisure. The average

young Chinese woman looked forward only to an arranged marriage in

which she would hold little status until she produced male heirs,

a marriage in which she would be expected to serve her mother-in-law

and submit to her husband. Her life revolved around the necessity

for obedience -- as a daughter, to her parents; after marriage, to

her husband; in widowhood, to her son (Pascoe, 1990).

Women in North America signing up for surgery:

During the 1980s, cosmetic surgery had become the fastest-growing

medical specialty in North America. At the end of that decade, more

than 2 million U.S. women (1 in 60, according to Faludi, 1991) had

had surgical breast implants. More than 100,000 had undergone liposuction

surgery.  According to one survey, these women were not rich about half made

less than $25,000 per year, and took out loans to pay their surgery

bill. Many women undertook the dangers and heavy costs of surgery

in order to achieve or try to maintain a standard of beauty they felt

necessary for attracting or holding a man. Where did they get the

idea that such drastic measures might be necessary? From millions

of magazine advertisements featuring impossibly-shaped women, and

from the countless "personal" ads in which men specified that they

were looking for a woman who was "attractive and thin" (Smith, Waldorf,

& Trembath, 1990). A representative survey of more than 800 adult

U.S. women in 1995 showed that women held substantially higher levels

of dissatisfaction with their bodies than had been observed in a similar

survey a decade before and nearly half the women reported overall

negative evaluations of their appearance (Cash & Henry, 1995).

According to one survey, these women were not rich about half made

less than $25,000 per year, and took out loans to pay their surgery

bill. Many women undertook the dangers and heavy costs of surgery

in order to achieve or try to maintain a standard of beauty they felt

necessary for attracting or holding a man. Where did they get the

idea that such drastic measures might be necessary? From millions

of magazine advertisements featuring impossibly-shaped women, and

from the countless "personal" ads in which men specified that they

were looking for a woman who was "attractive and thin" (Smith, Waldorf,

& Trembath, 1990). A representative survey of more than 800 adult

U.S. women in 1995 showed that women held substantially higher levels

of dissatisfaction with their bodies than had been observed in a similar

survey a decade before and nearly half the women reported overall

negative evaluations of their appearance (Cash & Henry, 1995).

Young women starving themselves in Argentina:

Maria, an 18-year old Argentine

high school student, became obsessed with being thin after an ex-boyfriend

called her "fatso" in front of her friends. She starved herself for

weeks, and wrapped nylon stockings and plastic bags around her body

to "sweat off" weight. Soon she appeared gaunt and pale, with sunken

cheeks and protruding ribs. She developed black patches under her

eyes from malnutrition, stopped menstruating, and could not tolerate

the sight of food. Finally, she says, "After three months, people

began asking if I had AIDS--I was so glad then. I thought, that means

I'm as thin as a model now. Now I'm beautiful." (Faiola, 1997, p.

A24).

Maria's case is an example of an

eating disorder called anorexia nervosa: an obsession with thinness

and a distorted body image that leads to self-starvation. People who

suffer from anorexia tend to "feel fat" even when severely underweight,

so they starve themselves in order to achieve the thinness they crave.

A related eating disorder, bulimia, is characterized by a pattern

of binge overeating followed by self-induced purging through dieting,

vomiting, or the use of laxative. This disorder too revolves around

an obsession with food and with body weight. Both disorders have,

according to media reports, reached epidemic proportions in Argentina,

where they are jointly known as "fashion model syndrome" and may have

the highest incidence in the world (Faiola, 1997). They are most common

among young, middle-to-upper class women, although the percentage

of male cases has increased in recent years from 5 to 12 percent.

If I were teaching my psychology

of women course now, I would ask my students to look for the common

threads that link these examples. Here are some things I hope they

would notice [OVERHEAD: Slide not available]:

*These very different cultures

all include strong ideas about what it means to be feminine.

*The notions of femininity have

overlapping themes:

--subservience to and dependence on men (especially the husband),

--the importance of beauty,

--restrictions on movement, strength (and other freedoms).

A course that incorporates multiple cultural perspectives can:

--show how certain issues are shared for women in many cultures

--show how certain issues are structured or interpreted

or coped with differently in different times and places.

--help students to understand how interpretations can become "real";

--help us and our students to break out of habits of thought and become

open to new ways of thinking about issues.

So by incorporating multicultural perspectives, we may discover/define/construct

some kind of balance between cultural universals and particulars in

the psychology of women and gender, and provide students with

a appreciation of diversity and a wider knowledge of the world.

I am going to give you examples

of how this approach can be used in four areas. These are areas in

which a reasonable amount of data from different cultures exist, and

which are obvious topics for courses on the psychology of women or

Gender:

*what is meant by gender categories

*gender stereotypes and ideologies

*violence against women

*power and gender

A. What do we mean by gender categories?

-We usually use 2 mutually exclusive categories to define gender

and we divide everyone into one or the other: female or male.

- e.g., what happens when a baby is born with ambiguous genitalia

...

Nothing puts the social construction

of gender in to such sharp relief for us as looking at societies in

which gender in discussed, not in terms of two categories (feminine

or masculine) but in terms of three or more categories. For those

of us who have grown up thinking of gender as a fixed, binary concept,

it may be difficult to imagine a third gender, or to imagine a society

in which an individual's gender is considered fluid or changeable,

or to imagine gender as a continuum instead of distinct categories.

These difficulties of imagination

are exactly the ones that encumbered anthropologists and other chroniclers

of North American Indian societies. When these anthropologist outsiders

encountered individuals in Indian societies who apparently had an

"intermediate" gender status, accomplished by combining or mixing

the attributes and behaviors of females and male, they tried to fit

these individuals into their own culturally-based understanding of

gender.  Thus,

they used terms such as "man-woman" and "halfman-halfwoman" to translate

the Indian terms for such individuals: nadle, winkte, heemaneh.

Yet it now appears that these translations were misleading, limited

by the anthropologists' own notions of gender. Instead, the terms

seem to describe a distinct third gender -- one that is not simply

a mixture of masculine and feminine, but defined separately from them

(Callender & Kochems, 1983; Fulton & Anderson, 1992). The person is

not a man dressing and acting like a woman, nor a woman dressing and

acting like a man, but a man or woman who has adopted a third role

-- that is neither feminine nor masculine. Thus,

they used terms such as "man-woman" and "halfman-halfwoman" to translate

the Indian terms for such individuals: nadle, winkte, heemaneh.

Yet it now appears that these translations were misleading, limited

by the anthropologists' own notions of gender. Instead, the terms

seem to describe a distinct third gender -- one that is not simply

a mixture of masculine and feminine, but defined separately from them

(Callender & Kochems, 1983; Fulton & Anderson, 1992). The person is

not a man dressing and acting like a woman, nor a woman dressing and

acting like a man, but a man or woman who has adopted a third role

-- that is neither feminine nor masculine.

These individuals were not simply

"cross-dressing" (i.e. men or women dressing in the clothing of the

other gender) but were wearing clothing appropriate to their third

gender status: clothing that was a mixture of the items usually worn

by women and men. More important than sexuality seems to be the

adoption of particular forms of work, social habits, dress.

For example, anthroplogist John

Honigman (1954) notes that among the Kaska Indians of the Canadian

subarctic, gender transformations were ometimes necessitated by the

division of labor. They depended on large game hunting to survive.

If a couple had no sons to help them with this task, the performed

a ceremony of gender transformation on their youngest daughter. They

tied the dried ovaries of a bear to a special belt for her, to prevent

her from menstruating or becoming pregnant. These girls grew up developing

exceptional hunting skills, participated as men in the male-only sweat

baths, and were accepted by men on the basis of their activities.

Some anthropologists now feel that

individuals of the third gender, by adopting a role that bridged the

categories of female and male, became regarded as intermediaries for

dangerous passages between categories. Thus, these third gender individuals

often presided over transformational events such as birth, marriage

and death and were highly valued by their communities as arbiters

of continuity in a precarious world (Fulton & Anderson, 1992).

The idea that there can be more

than two genders is not limited to North American Indian societies.

In Samoa, for example, there is a third gender category of person

called fa'afafíne, meaning "the way of women." These are

males who dress in women's clothing and are often included in female

activities. However, these individuals do not "pass" for women, nor

do they follow the rules that are understood to be in place for "proper"

women. Rather, they act as jesters who mock certain gender restrictions

and can violate them with impunity. For instance, a Samoan girl may

whisper some suggestive remark about a passing boy -- perhaps a sexual

comment about some feature of his anatomy -- to a fa'afafíne.

The fa'afafíne not bound by the same restrictions of propriety

as the girl, will then make a loud joke out of her comments, attracting

the attention of the boy (Mageo, 1992).

Other examples of third, or even

fourth, gender categories exist (the hijras of India, the "manly-hearted

women" of some North American Indian groups). Some good references

are included in the list I have give you.

For students, it is interesting

to note not only the diversity in thinking about gender and in the

institutionalization of gender across cultures, but also the ways

in which anthropologist-outsiders reacted to these differences. What

did they see? What did they fail to notice? How was their "seeing"

influenced by their own culturally-based assumptions? For example,

anthropologist Martha Ward (1996) notes that virtually nothing is

known about the women who became the wives of the female chiefs or

"manly hearted women" they were simply taken for granted and ignored

by male anthropologists who "assumed" that anyone taking on the role

of a man needed a wife.

B. Gender stereotypes and ideologies

In Japan, girls are taught from

an early age that femininity involves modesty in speech. The appropriate

and natural speaking style for females, they learn, involves softness

of voice, reticence, extreme politeness, and covering the mouth when

talking or laughing. So well do they learn these lessons that, as

adult women, their speech is often characterized by deference and

accommodation. For example, when one researcher studied the speaking

style of popular television cooking show hosts in Japan, she found

striking gender differences in speaking style. The male host tended

to give authoritative directives to his television underlings, telling

them to "add this to the bowl," or "stir this now." The female host,

on the other hand, was likely to phrase her directive in a more deferential

way, such as "if you would now do me the favor of stirring this" (Smith,

1992).

Every cultural group has its own

version of gender stereotypes: socially shared beliefs that certain

qualities can be attributed to individuals, based on their membership

in a gender category, and gender role ideologies, prescriptive beliefs

about how females and males should behave.

- There is quite a bit of cross-cultural data on these topics, so

it makes a good example and allows us to raise some interesting questions

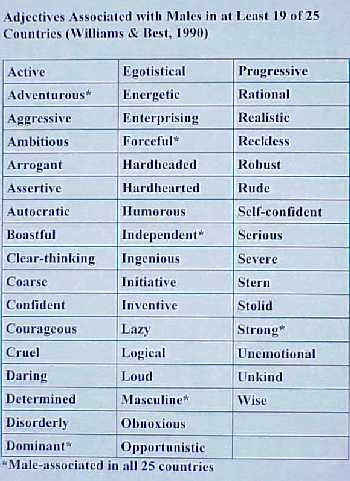

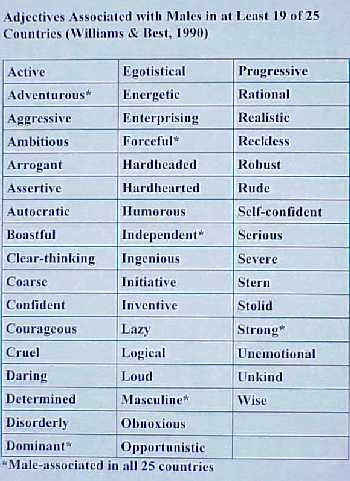

- U.S. research: More than two decades ago, researchers found

that American university students, asked to categorize 300 adjectives

as being typically associated with women or men, agreed strongly on

a cluster of 30 adjectives for women and 33 for men (Williams & Bennett,

1975). Women were, for instance, described as dependent, dreamy, emotional,

excitable, fickle, gentle, sentimental, and weak; Men were thought

to be adventurous, aggressive, ambitious, boastful, confident, logical,

loud, rational, and tough.

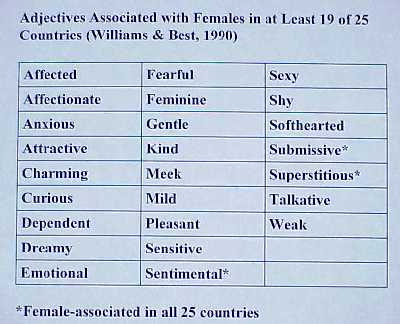

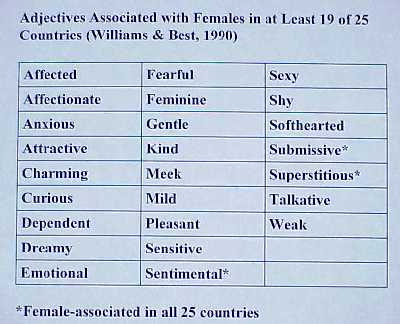

-Cross-cultural comparisons: Researchers in Canada (Edwards

& Williams, 1980) and Britain (Burns, 1977) found similar patterns,

and a study of gender stereotyping in thirty countries showed considerable

cross-cultural uniformity in the patterns of adjectives associated

with women and men (Williams & Best, 1982). Studies of adults in 25

countries showed that six (out of a possible 300)

items were associated with men in every country: adventurous, dominant,

forceful independent, masculine, and strong (Williams & Best, 1990).

Only three were associated with women in every country:

sentimental, submissive, and superstitious. These overheads show the

adjectives that were associated with men and with women in at least

75% (i.e., 19) of the 25 countries studies by Williams and Best.

When Williams and Best scaled the

items for affective meaning, along the dimensions of favorability,

strength, and activity, they found the following [OVERHEAD: Slide

not available]:

- no cross-cultural consistency

in the relative favorability of the female-and male-associated traits.

In some countries, such as Japan, South Africa, Nigeria, Malaysia,

and Israel, the male stereotype was associated with considerably more

favorability than the female stereotype. However, in other countries,

such as Italy, Peru, Australia, Scotland, and India, the female stereotype

was most favorable

- in all countries, the male stereotype

items were more active and stronger, and the females stereotype items

were more passive and weaker. These strength and acitivity differences

were greater in countries that were:

- socioeconomically less developed

- literacy was low

- the percentage of women attending

university was low

- when overall differentiation

scores were calculated for the three affective meaning dimensions

combined, there was a lot of variation among countries in this differentiation.

The countries in which the female and male stereotypes seemed to be

perceived as most different were Nigeria, South Africa, Malaysia,

and Japan; they were seen as least different in France, India, Finland,

and Trinidad.

How can we help our students make

sense of the similarities and differences in gender stereotypes and

ideologies across cultures? As students try to form a "right" answer

to the question about the universality of gender stereotypes, I try

to encourage them to step back from that question and the need for

closure on it, and focus instead on how the way we ask research questions

affects the shape of the answers.

For instance some of the possible reasons for cross-cultural similarity:

[OVERHEAD: Slide not available]

Some of the apparent similarity

across cultures may be due to the use of university students -- a

privileged group, often not particularly representative of cultural

attitudes, and often more influenced than others in the culture by

"modern" thought -- in each culture to complete the questionnaires.

Also, university students may be

less representative of the population in some countries than others

as university education is much more available in certain countries

than others, and differentially available to women and men in some

cultures.

Another factor contributing to

the similarity across cultures may be the status difference between

women and men that is common to most of them.. In most cultures, men

are accorded somewhat higher status than women--and researchers have

shown that high-status people are usually judged to be more agentic

(self- and individual achievement-oriented), while low-status people

are judged to be more communal (relationship-oriented; Conway, Pizzamiglio,

& Mount, 1996). This difference parallels stereotypical gender differences.

Some of the things that could contribute to cross-cultural differences:

[OVERHEAD Slide not available]

Domains

Judith Gibbons, Beverly Hamby and

Wanda Dennis (1997) point out that cultures vary in the domains in

which women's and men's roles differ or in the settings in which such

roles are relevant (e.g., marriage, family, employment, education,

politics). If we ask about certain domains we may find cultural differences

but not if we ask about others. And in some cultures we may not know

enough about these domains to ask the right questions. "In order to

develop an instrument with a high level of salience, one would first

need to describe the domains relevant for a particular culture's gender

toles, and then assess beliefs using these ... constructs"

(Overhead: Tibetan example, not available)

Settings.

Some settings are simply irrelevant

in some cultures. For example, as Gibbons and her colleagues (1997)

note, it is no use asking "On a date, the boy should be expected to

pay all expenses" (AWS item) in a setting such as Iran, where dating

does not exist.

Meaning

Setting aside the problem of translation,

which is a major one in cross-cultural research, even within a language,

the same terms may have different meanings for different ethnic groups.

[OVERHEAD: not available]-e.g. Hope Landrine, Elizabeth

Klonoff and Alice Brown-Collins (1995) asked White women and Women

of Color to rate themselves on adjectives taken from the Bem Sex Role

Inventory. The two groups did not differ on their self-ratings on

these items. However, they apparently meant different things by at

least some of the items. For instance, by "passive" the largest percentage

of European American women said they meant "am laidback/easy-going",

while the largest percentage of Women of Color said they meant "don't

say what I really think". And by "assertive" White women were more

likely to mean "stand up for myself" while Women of Color were more

likely to mean "say whatever's on my mind".

Judith Gibbons and her colleagues

(1993) report another example of different meanings assigned to the

same concept. In their research, adolescents from Guatemala, the Philippines,

and the U.S. depicted the ideal woman as working in an office. However,

further analysis revealed that "in the Philippines office work was

associated with glamour, in the United States with routine and boredom,

and in Guatemala with the betterment of the family".

And if the item is not meaningful

at all to the respondent? Gibbons, Hamby and Dennis (1997) have

shown that the less meaningful an item is to respondents, the less

extreme is the response to it on a scale. Thus, "meaningless" items

may contribute to "no-difference" findings. Conversely, they note

that adding items or scales that are developed to be particularly

meaningful to the cultural group under study is likely to result in

more findings of differences.

Besides the similarities across

cultures in the content of gender stereotypes, there are also some

interesting similarities in the variables with which these stereotypes

correlate [OVERHEAD: Slide not available] :

For one things, across a wide range

of cultures, many researchers find that girls hold fewer traditional

gender attitudes than boys do. Is this a universal phenomenon? Not

necessarily, according to a review by Gibbons, Hamby and Dennis (1997).

Researchers have found no gender differences in gender-role ideology

in Malyasia, Pakistan or Spain, and have even found more liberal attitudes

among men than women in samples from Brazil and Dublin.

| |

Judith Gibbons, Deborah

Stiles, and their colleagues have also demonstrated that adolescent

daughters and sons of mothers who work outside the home hold

less conservative gender role attitudes in societies as diverse

as Mexico, Spain, Iceland, the U.S. Similarly, John Williams

and Deborah Best have shown, in their 14-country study of gender

ideology, that idealized gender roles are less differentiated

in societies in which a higher percentage of women work outside

the home and are university-educated (Williams & Best, 1990).

Gibbons, Stiles and Shkodriani (1991) showed that adolescents

from wealthier, more individualistic cultures report less traditional

gender role attitudes than adolescents from poorer, more collectivist

countries. |

Why might such correlations exist?

What variables are confounded here? Scales were developed in wealthy

developed individualistic countries for the most part. These variables

are often confounded with each other and with literacy, education,

employment of women outside the home.

So, what I am trying to show my

students is that researchers have provided some important beginnings

of an answer to the question about cross-cultural variation in ideas

about gender, but that it is important to keep paying attention to

the way that questions are being asked.

C. Violence against women

Agnes, a teacher whose husband

was also a teacher "said the violence began a few years after

she got married, when she caught her husband in bed with a teenage

girl. He began to beat her every evening. He forced her to give him

her paycheck. He called her his slave. For about two years, the violence

eased, but alcoholic rages and financial irresponsibility again became

the norm. And the beatings got worse." Nonetheless, Agnes

did not tell anyone about the beatings, even those closest to her

because, she said, "I was so scared, and I was feeling so

embarrassed. I did not want people to know about it." (Buckley,

1996, p. A26).

Where in the world did this story

happen?

In

what country are women so vulnerable to violence from their husbands

that they bear it for years without leaving and without telling anyone

about it? This particular story happened in the African country of

Kenya. However, a perusal of the research on wife abuse will show

that it could have happened absolutely anywhere that this is a very

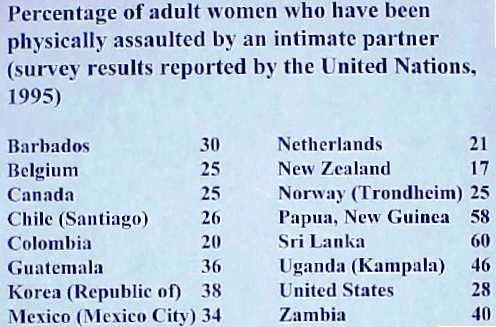

common story in almost every country of the world. While it is very

difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the frequency of domestic

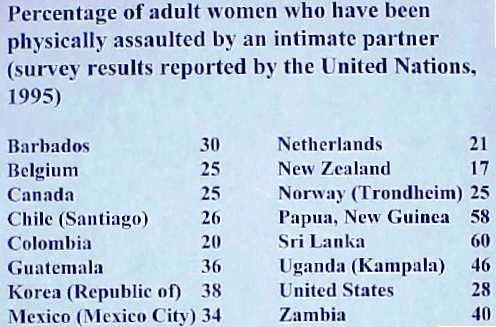

violence, surveys in various countries suggest that the percentage

of women reporting physical abuse by a male partner may range from

a minimum (!) of about 17 to 25 percent (e.g., studies in New Zealand,

Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway) to a high of 55 to 60 percent

or more (e.g., studies in Japan, Ecuador, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, some

parts of Mexico and of India) (Neft & Levine, 1997). In

what country are women so vulnerable to violence from their husbands

that they bear it for years without leaving and without telling anyone

about it? This particular story happened in the African country of

Kenya. However, a perusal of the research on wife abuse will show

that it could have happened absolutely anywhere that this is a very

common story in almost every country of the world. While it is very

difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the frequency of domestic

violence, surveys in various countries suggest that the percentage

of women reporting physical abuse by a male partner may range from

a minimum (!) of about 17 to 25 percent (e.g., studies in New Zealand,

Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway) to a high of 55 to 60 percent

or more (e.g., studies in Japan, Ecuador, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, some

parts of Mexico and of India) (Neft & Levine, 1997).

While there is a disheartening

universality to the statistics on violence against women worldwide,

the violence can take different forms in different cultures, and I

think it is worth looking at these differences. For example, I spend

some time focusing on the institutionalization of wife-murder in certain

cultures:

Institutionalized wife-murder

*for money: dowry deaths

in India. One country in which the notion of marriage

as an economic arrangement is still strong is India, where parents

may sometimes literally bribe men to marry their daughters. It is

socially shameful and often economically distressing to have a daughter

for whom a suitable husband cannot be found, so parents entice potential

bridegrooms with promises of dowries of cash and/or household goods.

Frequently, in fact, parents go deeply into debt to marry off their

daughters. However, even after the marriage has taken place, a husband's

family may be unsatisfied with the dowry. They may pressure the new

wife to get more goods from her parents, making her life miserable

with insults and harassment if she is unwilling or unable to do so

(Narasimhan, 1994). The young woman must endure the suffering because

she cannot leave the marriage without bringing severe disgrace on

her family and herself.

Such situations often end with

the death of the new bride. Sometimes, in desperation because the

mistreatment has become unbearable, she commits suicide. Often, however,

she is murdered: doused with kerosene by her in-laws and set on fire.

The death is reported to authorities as a "kitchen accident"-- an

explanation that has some surface plausibility because middle-class

homes often use kerosene stoves for cooking. In 1995, the Indian government

reported 7,300 such "dowry deaths" (Neft & Levine, 1997).

A 1961 law prohibiting dowries

appears to have had little effect in the face of strong traditions

and the difficulty of proving what happened. A more stringent law,

passed in 1986, states that, in every unnatural death of a woman during

the first seven years of marriage, the husband or in-laws must be

presumed responsible by the courts. Yet convictions under this law

are rare, and dowry deaths continue to increase.

*for "honor": "honor

killings": A strong tradition exists, discernible in

many societies, that if a woman "dishonors" her husband (or sometimes

her father) by becoming sexually involved with man to whom she is

not married, it is legitimate for her to be killed. The buried remnants

of such a tradition can be found in North America, where a husband

who kills his wife in a "jealous rage" after discovering her adultery

may in some communities be regarded with more sympathy than outrage.

The tradition is more obvious, and reflected in the legal system,

in certain other countries.

In a famous case in Brazil, a man

arrived at a hotel where his wife was staying with another man and

asked the bellman to bring him to the couple's room. When the wife's

lover opened the door at the bellman's request, the husband stabbed

him repeatedly in the chest, killing him. The wife ran naked from

the room and into the street, where she was pursued by her husband,

caught, and stabbed to death.

An all-male jury accepted the argument

that the husband in this case had acted in legitimate defense of his

wounded honor and acquitted him of the double murder. The decision

, after being upheld by an appeals court, was later overturned by

Brazil's highest court, the Superior Tribunal of Justice. The Tribunal

ordered a new trial, noting that murder could not be considered a

legitimate response to adultery and that "what is being defended in

this type of crime is not honour but 'self-esteem, vanity and the

pride of the lord who sees his wife as property'." (Thomas, 1994,

p. 33).

Feminist activists in Brazil, who

had for decades been fighting to de-legitimate the "honor defense"

and the proprietary attitudes toward women underlying it, were buoyed

by this decision. However, when the new trial was conducted in 1991,

the husband was once again acquitted of the double killing on the

grounds that he had been legitimately defending his honor. Thus, in

Brazilian culture, wife murder was still considered an appropriate

response to alleged unfaithfulness; a husband could kill his wife

with impunity under such circumstances.

"Honor killings" to wipe away the

shame brought to a husband, father or brother by a female relative's

premarital or extramarital sex are a part of life in certain parts

of the Islamic world. In Palestinian villages, according to some estimates,

about 40 women a year die at the hands of a male relative who then

becomes a hero for clearing his family name. This type of killing

is not necessarily done in a rage, but is planned and premeditated.

An errant daughter or wife may be lured home with the promise that

all is forgiven, then cold-bloodedly murdered. Such killings also

happen in other Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia and Sudan, and

even sometimes among families who have emigrated to non-Muslim countries

(Brooks, 1995). Furthermore, although they are not legally sanctioned,

wife-murders that arise from jealousy, outraged pride, or wounded

egos, certainly happen with some frequency in most countries, including

the United States and Canada. In both countries, wives are the most

frequent victims of fatal violence in families and such fatal violence

is most likely to occur when the woman tries to leave an abusive husband.

Other forms of violence against

women can also be discussed in a global framework; for example, there

is widespread evidence of the prevalence of rape in many countries.

[OVERHEADS: Not available}

Common themes?

While some stories of male violence

against the women in their families are more horrific than others,

I try to get my students to see some common themes that run through

them:

| |

-the woman

is considered the man's property;

-the man is believed entitled to wield authority over the woman

and to punish her if she defies this authority;

-the family is viewed as a private institution where the man

rules and outsiders should not interfere;

-the woman is regarded as inferior to the man. |

These patriarchal cultural attitudes

emerge in the courtship violence documented in certain countries,

in the wife-beatings that occur all over the world, in dowry deaths

and honor killings. These attitudes are woven into the fabric of many

cultures, although their expression is more subtle in some times and

places than others and some individuals have been socialized with

a stronger "dose" of them than others in their culture. The point

of exposing students to the variety of forms that anti-female violence

can take is not to illustrate how bad "other" cultures are, but to

show how social-environmental factors can shape such behavior, and

how some of the same themes can be identified in various guises.

From a global, multicultural examination

of violence against women, students can learn that suchbehavior is

possible anywhere, but that it is shaped by culture. The social and

culturalenvironment, through the promulgation of particular attitudes

and values about families, shape the likelihood that children will

be raised in families where they witness or are victims of violence.

Similarly, culture shapes attitudes about the legitimacy of male domination

and female subordination, and about the social acceptability of using

violence in many situations. Will thepolice respond to and take seriously

a charge of spousal violence? If not, the abuser has more power. As

well, the availability of alternatives in the social environment affects

the power that the victim of violence has to leave the relationship.

Are there shelters for victims of abuse? Can a woman live safely on

her own? If not, the abuser has more power. Thus, power in interpersonal

relationships is, to some extent, shaped by the values and attitudes

promoted in the sociopolitical and cultural environment.

D. Gender and Political Power

Women have occasionally headed countries as monarchs: for instance,

Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria of England, Catherine the Great

of Russia. However, the first woman elected to lead a nation appears

to have been Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who became prime minister of what

is now Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1960. From 1960 until 1997,

31 women around the world were elected or appointed as heads of state

(Neft & Levine, 1997). If you have not heard of many of them, it is

because, for some, their terms of office were extraordinarily short.

For example, Kim Campbell, Sylvie Kinigi, Edith Cresson and Ertha

Pascall-Trouillot were, respectively, Prime Ministers of Canada, Bolivia,

France and Haiti for less than a year.

Women have occasionally headed countries as monarchs: for instance,

Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria of England, Catherine the Great

of Russia. However, the first woman elected to lead a nation appears

to have been Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who became prime minister of what

is now Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1960. From 1960 until 1997,

31 women around the world were elected or appointed as heads of state

(Neft & Levine, 1997). If you have not heard of many of them, it is

because, for some, their terms of office were extraordinarily short.

For example, Kim Campbell, Sylvie Kinigi, Edith Cresson and Ertha

Pascall-Trouillot were, respectively, Prime Ministers of Canada, Bolivia,

France and Haiti for less than a year.

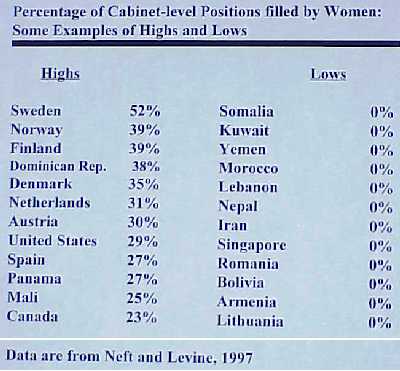

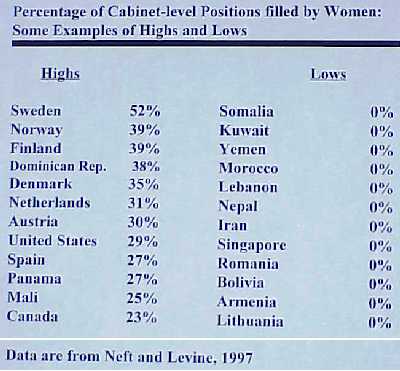

Women have been an increasing presence

in national legislatures worldwide. However, there is no nation in

which women hold half of such posts. Currently, the countries in which

women hold the highest percentage of seats in national legislatures

are Sweden (41%), Norway (39%), Finland (34%) and Denmark (33%). Canada

(19%) and the United States (11%) are far lower; many other countries

are lower still (e.g., France and Singapore have 5%; Iran and Kenya

have 4%; Somalia and Kuwait have none). [OVERHEAD - WOMEN

IN MINISTERIAL LEVEL POSITIONS - Slide Not available]

I have been doing some cross-cultural

research on women's perceptions of their possible selves as political

leaders and holders of other powerful positions, and one of the things

that is clear from this research is that young women in the United

States and in other countries feel that power and femininity do not

go together easily there is a tension between the two.

This is not surprising, given the

literature on gender stereotypes that we have just examined, and given

the shortage of female leaders who are available to act as role models.

Young women in countries such as the United States, Spain, and Argentina

are apparently aware of the tension between the requirements of femininity

and power. When asked to describe what they would be like if they

held powerful positions such as political leadership or corporate

presidencies, many female university students in these countries viewed

political leadership as an unlikely possibility for them. They also

stressed that, should they ever hold such a position, they would try

to balance the requirements of femininity and power: they would be

compassionate even though powerful, kind to subordinates even though

demanding, nice even though tough (Lips, 1996; Lips, de Verthelyi,

& Gonzalez, 1996). Some worried that others would not like them in

these roles a worry that, given the media reactions to female politicians,

seems well-founded. A sampling of their comments appears in the OVERHEAD.

When respondents in the United

States and Spain were asked for men's thoughts about powerful women,

those from both countries listed negative attributes: "more obsessed

[than men] in reaching power," "pedantic and authoritarian," "[they]

try to have power like men do, but without doing it like real women"

(Diaz Zuniga, Sattler, & Lips, 1997).

Whereas our research shows commonalities

among samples of women in different cultures, it also shows differences.

For example, women in our U.S. sample anticipated more relationship

problems associated with being a political leader than their male

counterparts did. However, in our sample from Spain, the women did

not anticipate any more problems than the men did and were significantly

less likely than U.S. women to mention the possibility of such problems

(Back, Diaz & Lips, 1996). In a comparison of another mainland U.S.

(Virginia) sample with a sample of women from Puerto Rico, we found

that, while the women from both samples anticipated the same level

of relationship problems associated with powerful positions, only

for the Virginia sample was such anticipation linked to a stated lower

likelihood that they could achieve such a leadership position (Lips,

1998).

It is not surprising that women

in different cultures share, to some extent, ambivalent feelings about

becoming political leaders. But what cultural factors may influence

the differences the ways women react to this possibility?

We have postulated that some of

the differences between the mainland U.S. samples and those in Spain

and Puerto Rico may be related to cultural differences on the dimension

of independence-interdependence (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Mainstream

U.S. culture is apparently one of the most independence-oriented cultures,

emphasizing a notion of the self as unique and separate. Latin American

cultures and Spain, on the other hand, are sometimes found to be more

interdependence-oriented, emphasizing a sense of self that encompasses

various communities of which the individual is a part: family, work

groups, friendship groups. In the more independence-oriented culture

of the U.S. mainland, then, women may be likely to feel more individually

responsible for making their relationships work, and to feel pressure

and blame when they do not. In the more interdependence-oriented cultures

of Spain and Puerto Rico, however, women may be more secure in certain

of their core relationships, allowing them to contemplate conflict

that may occur in others.

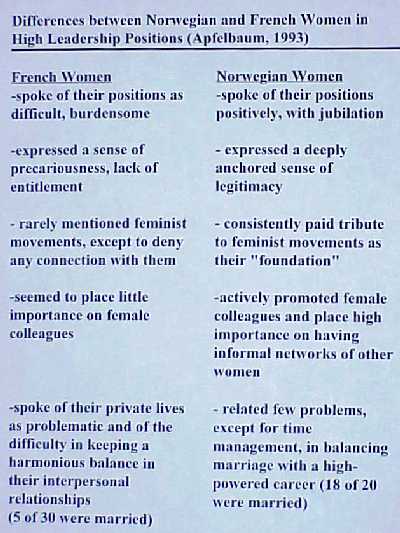

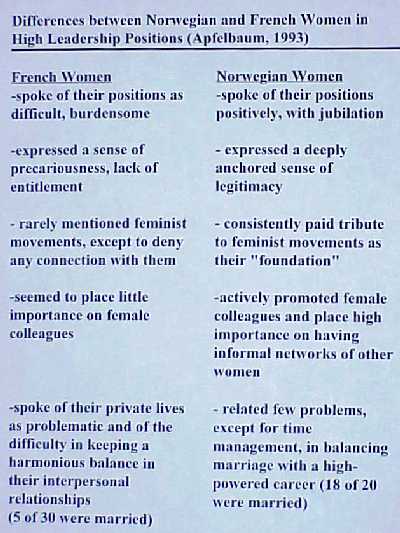

Erica

Apfelbaum (1993) investigated some ways in which the particular form

taken by women's experience of occupying a leadership position is

shaped by her culture and her times. Apfelbaum conducted in-depth

interviews with 50 women leaders in France and Norway. She discovered

that in these two western European countries, powerful women reported

very different experiences. Here are some of the differences she found

between the two samples; Erica

Apfelbaum (1993) investigated some ways in which the particular form

taken by women's experience of occupying a leadership position is

shaped by her culture and her times. Apfelbaum conducted in-depth

interviews with 50 women leaders in France and Norway. She discovered

that in these two western European countries, powerful women reported

very different experiences. Here are some of the differences she found

between the two samples;

In France, the women leaders spoke

of their lives as difficult, burdensome and filled with conflict and

suffering. In Norway, by contrast, the women spoke of their roles

positively and with jubilation, ETC. It appears that leadership

and power mean different things to the women in these tow countries.

What could account for the differences

in tone between powerful women in these two countries? [OVERHEAD:

Not Available] Part of it can be explained by the differing

history of the two countries. Power for women is a much older and

more established idea in Norway than in France. Norwegian women obtained

the vote in 1913, had women representatives in local assemblies beginning

in 1967, and have consistently had the support of major political

parties in their push to gain equality. It is a country in which a

woman has been Prime Minister in three different governments and in

which 39 percent of cabinet posts are held by women. In France, women

did not win the right to vote until 1944, and they still hold only

a small proportion of legislative seats and 13 percent of cabinet

posts. The few token women in high positions are used as examples

to "prove" that women are represented at all levels and to discourage

further claims.

Clearly, the presence of women

who have broken ground as pioneers and role models changes the social

landscape for the women who come later, providing them with a legacy

of increased confidence and legitimacy. In France, Apfelbaum noted

that the women leaders who had obtained their positions in the 1980s

were more optimistic and less lonely than those who had obtained their

positions in the previous decade. In Norway, where women had a longer

history of role models on which to draw, the women "expressed a deeply

anchored sense of legitimacy that was totally alien to French women

of the first generation and just evolving for the second" (Apfelbaum

1993, p. 419).

Cultural attitudes about power

may also help to explain the differing experiences of Norwegian and

French women in leadership positions. In Norway, political life apparently

revolves around the idea of "turnover" the idea that power is transitory,

and that a leader easily "passes the torch" to a successor. The power

built into a leadership position is not a core part of the leader's

identity. Thus, men may not be very threatened by the notion of sharing

leadership with women. In France, on the other hand, the political

power structure is strongly identified with men, and there is no comparable

notion of easy turnover (Apfelbaum, 1993).

Perhaps as a result of the sociohistorical

differences between their two countries, Norwegian and French women

leaders differed dramatically in two other ways: their allegiance

to feminist movements, and the ease with which they combined their

high-profile positions with marriage. Norwegian women leaders of all

political persuasions consistently paid tribute to feminist movements

as "the foundation from which emerged the means to fight for the integration

of women in the public arena" (Apfelbaum, 1993, p. 421). The French

women, on the other hand, did not mention feminist movements except

for the purpose of denying any connection with them. Congruent with

these differing emphases on feminism, Norwegian women were much more

likely than French women to actively promote their female colleagues,

to respond actively and combatively to sexual harassment and everyday

sexism, and to place high importance on the friendship and support

provided by informal networks of other women.

The casual observer might think

that these combative, feminist-oriented Norwegian women would be less

likely than their French counterparts to be able to maintain their

close relationships with men. Nothing, found Apfelbaum (1993), could

be further from the truth. While 18 of the 20 Norwegian women were

married when interviewed, only five of the 30 French women were. Most

of the Norwegian women claimed to have had few problems balancing

marriage with their high-powered career, except for the logistical

ones involving time management. However, the French women were less

sanguine about their private lives. "Almost without exception, they

spontaneously raised the issue of their private life as a problematic

one and spoke at length about the burdens, the tensions and the difficulty

of keeping a harmonious balance in their interpersonal relations with

their companions. In this domain, they seemed vulnerable and insecure:

The danger of losing a companion was omnipresent, and deep down they

knew that being single was the price they might have to pay. French

men still seem unable to cope with the social comparison involved

once their wives become too visible." (Apfelbaum, 1993, p. 423). Apfelbaum

notes that the French tradition of male-female intimate relationships

is strongly based on romance, seduction, chivalry, and game-playing

all of which involve notions of conquest and dominance and of unequal

positions between women and men. Perhaps, she speculates, such cultural

traditions mitigate against the easy acceptance in France of relationships

in which the woman is visibly more powerful than the man.

The contrast between the leadership

experience for women in Norway and France suggests that holding power

is likely to involve major social and personal sacrifices for women

unless it is done within a cultural context where female leadership

is not unusual and female political participation is strong. It also

suggests, however, that such a context may be more difficult to achieve

in some cultures than in others. Given the discrepancies in the leadership

experiences of women from two western, European democracies, we can

only begin to glimpse the possible differences in the experiences

of women whose cultures diverge even more widely.

In Conclusion:

I have tried to show how the incorporation

of different cultural perspectives can help students to understand,

on many levels, that gender is to a large extent what societies make

it and that cultures construct the meanings that individuals attribute

to their experiences. The point is not to have students learn everything

about gender or women in every culture, but to get a feel for the

range of similarities and differences that exist across cultures.

In closing, I would like to make

one final recommendation: that students in these courses be exposed

to first-person accounts, or life stories, of women (and men, for

courses on gender) in a variety of cultures. The stories make the

issues real, provide touchstones for remembering some of the points

and principles, and perhaps most important, help them to see the world

from alternative points of view in ways that few of us can accomplish

in the classroom. I've provided a list of possible sources of such

first person accounts, and I hope you will find them useful.

If we try to teach with an eye

to multicultural perspectives, we will never be satisfied that we

have given completely adequate treatment to any issue, we will never

be done with broadening our own horizons. Each turn of the kaleidoscope,

after all, provides a new vision, a new combination of shapes, colors,

and designs. Our challenge is to stay open to many different visions,

to resist our own desire for closure, that impatient desire for the

quick "right answer" that we find so frustrating in our students.

The rewards for doing so are a psychology of women and gender indeed,

an entire field of psychology that focuses on the world instead of

only a small part of it, and students who are aware that their worldview

is not the only one possible. The women that I described at the beginning

of this talk Amelia Edwards, Bessie Coleman, Mae Jemison, Rigoberta

Menchú-- took enormous physical and emotional risks to leave

behind their cultural blinders. Surely, we can take some intellectual

ones. |

Presentation

Scenes

|

|

Currently,

we look mainly at white, middle-class U.S. women and men in our courses

on the psychology of women and gender. How can we separate what goes

with being female or male from what goes with being white, middle-class,

American? We cannot. And this makes it look as though certain qualities

or behaviors that correlate with being female or male in this culture

are inevitably linked to sex or to gender. The title for this talk

was suggested by a quote from Australian literary scholar Sneja Gunew:

In trying to grasp the experiences of women from a variety of times

and places, "we should perhaps use the image of a kaleidoscope, where

each turn produces different patterns and no single element dominates"

Sneja Gunew (1991).

Currently,

we look mainly at white, middle-class U.S. women and men in our courses

on the psychology of women and gender. How can we separate what goes

with being female or male from what goes with being white, middle-class,

American? We cannot. And this makes it look as though certain qualities

or behaviors that correlate with being female or male in this culture

are inevitably linked to sex or to gender. The title for this talk

was suggested by a quote from Australian literary scholar Sneja Gunew:

In trying to grasp the experiences of women from a variety of times

and places, "we should perhaps use the image of a kaleidoscope, where

each turn produces different patterns and no single element dominates"

Sneja Gunew (1991). Men measure a woman's attractiveness by her obesity, and a young woman

is prepared for marriage in ways guaranteed to "fatten her up": the

least possible activity and the most possible food. By the time of

her marriage, the young woman may be so fat that she cannot walk,

only waddle. At the wedding, onlookers then will comment on how beautiful

she is, noting with approval the cracks in her skin caused by the

fatness and the difficulty with which she walks. Once married, a wife

is kept fat by consuming surplus milk from the herd -- often coerced

to do so by her husband when she has long past the point of satiation.

The wife leads a life of "leisure." She is assigned no heavy physical

work, rarely leaves home, spends her days in sexual liaisons with

a variety of men approved by her husband. These sexual relationships

cement economic ones: the obese, conspicuously consuming wife is both

a symbol and an instrument of her husband's economic prosperity (Tiffany,

1982).

Men measure a woman's attractiveness by her obesity, and a young woman

is prepared for marriage in ways guaranteed to "fatten her up": the

least possible activity and the most possible food. By the time of

her marriage, the young woman may be so fat that she cannot walk,

only waddle. At the wedding, onlookers then will comment on how beautiful

she is, noting with approval the cracks in her skin caused by the

fatness and the difficulty with which she walks. Once married, a wife

is kept fat by consuming surplus milk from the herd -- often coerced

to do so by her husband when she has long past the point of satiation.

The wife leads a life of "leisure." She is assigned no heavy physical

work, rarely leaves home, spends her days in sexual liaisons with

a variety of men approved by her husband. These sexual relationships

cement economic ones: the obese, conspicuously consuming wife is both

a symbol and an instrument of her husband's economic prosperity (Tiffany,

1982). According to one survey, these women were not rich about half made

less than $25,000 per year, and took out loans to pay their surgery

bill. Many women undertook the dangers and heavy costs of surgery

in order to achieve or try to maintain a standard of beauty they felt

necessary for attracting or holding a man. Where did they get the

idea that such drastic measures might be necessary? From millions

of magazine advertisements featuring impossibly-shaped women, and

from the countless "personal" ads in which men specified that they

were looking for a woman who was "attractive and thin" (Smith, Waldorf,

& Trembath, 1990). A representative survey of more than 800 adult

U.S. women in 1995 showed that women held substantially higher levels

of dissatisfaction with their bodies than had been observed in a similar

survey a decade before and nearly half the women reported overall

negative evaluations of their appearance (Cash & Henry, 1995).

According to one survey, these women were not rich about half made

less than $25,000 per year, and took out loans to pay their surgery

bill. Many women undertook the dangers and heavy costs of surgery

in order to achieve or try to maintain a standard of beauty they felt

necessary for attracting or holding a man. Where did they get the

idea that such drastic measures might be necessary? From millions

of magazine advertisements featuring impossibly-shaped women, and

from the countless "personal" ads in which men specified that they

were looking for a woman who was "attractive and thin" (Smith, Waldorf,

& Trembath, 1990). A representative survey of more than 800 adult

U.S. women in 1995 showed that women held substantially higher levels

of dissatisfaction with their bodies than had been observed in a similar

survey a decade before and nearly half the women reported overall

negative evaluations of their appearance (Cash & Henry, 1995). Thus,

they used terms such as "man-woman" and "halfman-halfwoman" to translate

the Indian terms for such individuals: nadle, winkte, heemaneh.

Yet it now appears that these translations were misleading, limited

by the anthropologists' own notions of gender. Instead, the terms

seem to describe a distinct third gender -- one that is not simply

a mixture of masculine and feminine, but defined separately from them

(Callender & Kochems, 1983; Fulton & Anderson, 1992). The person is

not a man dressing and acting like a woman, nor a woman dressing and

acting like a man, but a man or woman who has adopted a third role

-- that is neither feminine nor masculine.

Thus,

they used terms such as "man-woman" and "halfman-halfwoman" to translate

the Indian terms for such individuals: nadle, winkte, heemaneh.

Yet it now appears that these translations were misleading, limited

by the anthropologists' own notions of gender. Instead, the terms

seem to describe a distinct third gender -- one that is not simply

a mixture of masculine and feminine, but defined separately from them

(Callender & Kochems, 1983; Fulton & Anderson, 1992). The person is

not a man dressing and acting like a woman, nor a woman dressing and

acting like a man, but a man or woman who has adopted a third role

-- that is neither feminine nor masculine.

In

what country are women so vulnerable to violence from their husbands

that they bear it for years without leaving and without telling anyone

about it? This particular story happened in the African country of

Kenya. However, a perusal of the research on wife abuse will show

that it could have happened absolutely anywhere that this is a very

common story in almost every country of the world. While it is very

difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the frequency of domestic

violence, surveys in various countries suggest that the percentage

of women reporting physical abuse by a male partner may range from

a minimum (!) of about 17 to 25 percent (e.g., studies in New Zealand,

Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway) to a high of 55 to 60 percent

or more (e.g., studies in Japan, Ecuador, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, some

parts of Mexico and of India) (Neft & Levine, 1997).

In

what country are women so vulnerable to violence from their husbands

that they bear it for years without leaving and without telling anyone

about it? This particular story happened in the African country of

Kenya. However, a perusal of the research on wife abuse will show

that it could have happened absolutely anywhere that this is a very

common story in almost every country of the world. While it is very

difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the frequency of domestic

violence, surveys in various countries suggest that the percentage

of women reporting physical abuse by a male partner may range from

a minimum (!) of about 17 to 25 percent (e.g., studies in New Zealand,

Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway) to a high of 55 to 60 percent

or more (e.g., studies in Japan, Ecuador, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, some

parts of Mexico and of India) (Neft & Levine, 1997). Women have occasionally headed countries as monarchs: for instance,

Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria of England, Catherine the Great

of Russia. However, the first woman elected to lead a nation appears

to have been Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who became prime minister of what

is now Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1960. From 1960 until 1997,

31 women around the world were elected or appointed as heads of state

(Neft & Levine, 1997). If you have not heard of many of them, it is

because, for some, their terms of office were extraordinarily short.

For example, Kim Campbell, Sylvie Kinigi, Edith Cresson and Ertha

Pascall-Trouillot were, respectively, Prime Ministers of Canada, Bolivia,

France and Haiti for less than a year.

Women have occasionally headed countries as monarchs: for instance,

Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria of England, Catherine the Great

of Russia. However, the first woman elected to lead a nation appears

to have been Sirimavo Bandaranaike, who became prime minister of what

is now Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1960. From 1960 until 1997,

31 women around the world were elected or appointed as heads of state

(Neft & Levine, 1997). If you have not heard of many of them, it is

because, for some, their terms of office were extraordinarily short.

For example, Kim Campbell, Sylvie Kinigi, Edith Cresson and Ertha

Pascall-Trouillot were, respectively, Prime Ministers of Canada, Bolivia,

France and Haiti for less than a year. Erica

Apfelbaum (1993) investigated some ways in which the particular form

taken by women's experience of occupying a leadership position is

shaped by her culture and her times. Apfelbaum conducted in-depth

interviews with 50 women leaders in France and Norway. She discovered

that in these two western European countries, powerful women reported

very different experiences. Here are some of the differences she found

between the two samples;

Erica

Apfelbaum (1993) investigated some ways in which the particular form

taken by women's experience of occupying a leadership position is

shaped by her culture and her times. Apfelbaum conducted in-depth

interviews with 50 women leaders in France and Norway. She discovered

that in these two western European countries, powerful women reported

very different experiences. Here are some of the differences she found

between the two samples;