Radford University

Radford News

Latest News

-

Highlanders in the News: Week of Feb. 16, 2026

February 20, 2026

Matthew Bagley ’15 – aka musician Alexander Mack – enjoys a brush with Grammy glory; veteran seafarer Erica Custis ’99 gets props from Marine Log magazine; and journalist Marty Smith ’98 reflects on his past with the Post.

-

Jobs for Virginia Graduates event gives college careers some ignition

February 19, 2026

Held Feb. 12 at Kyle Hall, the statewide JVG Ignite competition – designed to demonstrate innovation, knowledge and preparation – saw five students receive $1,000 each in Radford University scholarship funds.

-

Radford University Board of Visitors will consider tuition and mandatory fees for the 2025-2026 academic year at its next quarterly meeting.

-

Highlander Highlights: Week of Feb. 9, 2026

February 13, 2026

Highlander Highlights shares with readers some of the extraordinary research and accomplishments happening on and off campus through the tireless work and curiosity of our students, staff, alumni and faculty.

-

Highlanders in the News: Week of Feb. 2, 2026

February 6, 2026

Radio IQ drops in on an arresting art installation at the Radford University Art Museum; Courtney Ballantine ’00 is Georgetown University Police Department’s new chief; and on the eve of her debut novel, Cassie Miller ’07 is named one of Publishers Weekly’s ‘Writers to Watch.’

-

Shadow Day 2026 – “Highlanders helping Highlanders”

February 3, 2026

Late last month, the Davis College of Business and Economics held its second Shadow Day, in which about 100 students met and spoke with 20 successful Radford graduates, through 40 separate sessions across the morning and afternoon of Jan. 23.

-

Highlander Highlights: Week of Jan. 26, 2026

January 30, 2026

Highlander Highlights shares with readers some of the extraordinary accomplishments happening on and off campus through the tireless work and curiosity of our students, faculty, staff and alumni.

-

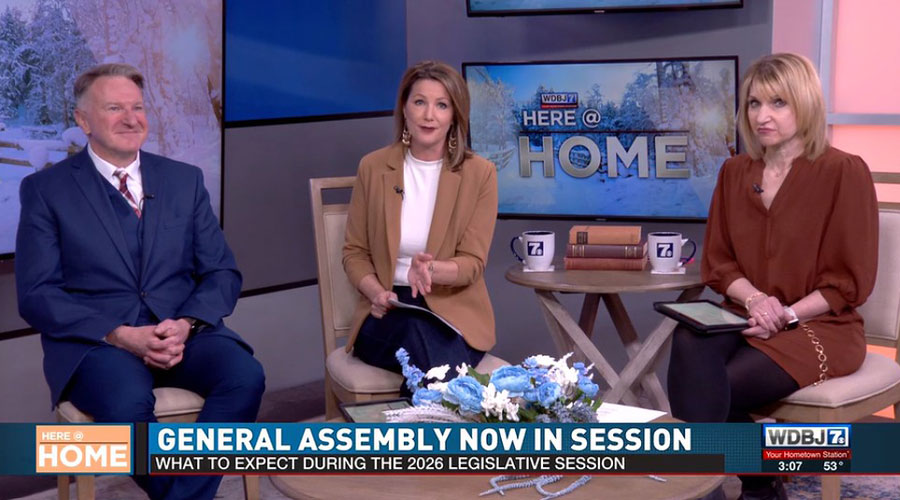

Highlanders in the News: Week of Jan. 19, 2026

January 23, 2026

The NCAA recognizes the efforts of Charlene Curtis ’76 and Alex Guerra ’11; Radford Department of Political Science Chair Chapman Rackaway previews Virginia’s 2026 General Assembly for WDBJ-7; and freshman Connor Worthington donates time to a worthy cause in his hometown.