Radford University

Radford News

Latest News

-

Radford College of Nursing negotiates agreement with Virginia Tech

February 26, 2026

High-achieving students at Virginia Tech now have a clearer and faster path to becoming Highlander nurses through a newly signed agreement.

-

The team will compete in the national championships March 6-8 in Cape Coral, Florida.

-

Radford students preparing for spring break trip to explore, research national parks in western U.S.

February 25, 2026

A group of Radford students are getting a unique opportunity to explore and conduct research at national parks.

-

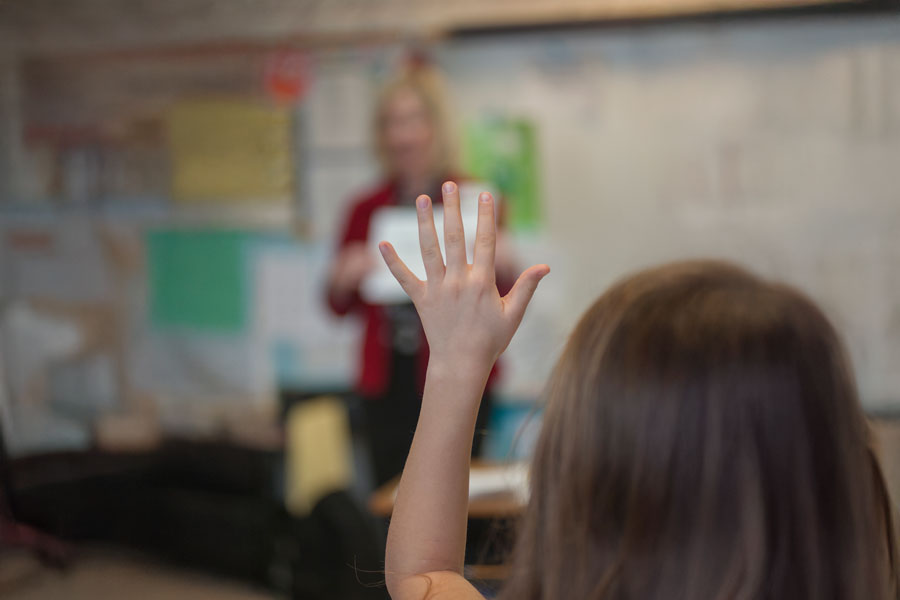

Radford University helps address Virginia’s teacher shortage through targeted licensure support

February 20, 2026

Radford University launched a targeted scholarship initiative to support provisionally licensed teachers in completing their licensure requirements.

-

Advocacy Day connects students with Virginia lawmakers

February 20, 2026

Radford University students spent Feb. 3-4 at the Capitol in Richmond, Virginia, for the university’s annual Advocacy Day.

-

Highlanders in the News: Week of Feb. 16, 2026

February 20, 2026

Matthew Bagley ’15 – aka musician Alexander Mack – enjoys a brush with Grammy glory; veteran seafarer Erica Custis ’99 gets props from Marine Log magazine; and journalist Marty Smith ’98 reflects on his past with the Post.

-

Jobs for Virginia Graduates event gives college careers some ignition

February 19, 2026

Held Feb. 12 at Kyle Hall, the statewide JVG Ignite competition – designed to demonstrate innovation, knowledge and preparation – saw five students receive $1,000 each in Radford University scholarship funds.

-

Radford University Board of Visitors will consider tuition and mandatory fees for the 2025-2026 academic year at its next quarterly meeting.