Radford University

College of Humanities and Behavioral Sciences

Build a Foundation for Lifelong Learning

The College of Humanities and Behavioral Sciences offers degree programs and individual classes designed to emphasize the liberal arts as a foundation for lifelong learning. We offer a number of degrees that lead to specific career paths in public relations, media, criminal justice, counseling, technical writing and forensics. View our academic programs

Academic Departments and Schools

Research and Outreach

The College of Humanities and Behavioral Sciences supports a variety of centers and labs focused on research and outreach to enhance educational and professional opportunities for our students and the community.

Our Facility

Hemphill Hall

Our College is housed in a state-of-the-art facility that opened in 2016. Hemphill Hall is the largest academic building on campus and features many professional-quality centers, labs, research space and classrooms.

Our College in the News

-

Highlanders in the News: Week of Jan. 19, 2026

January 23, 2026

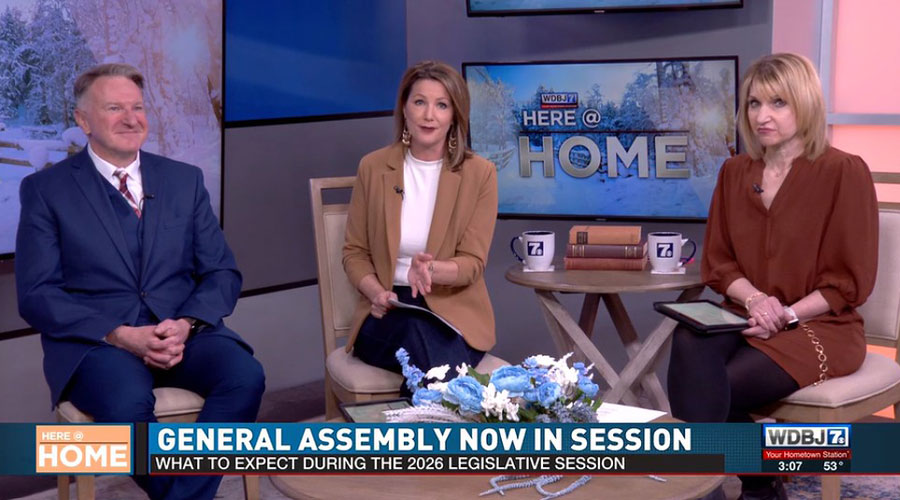

The NCAA recognizes the efforts of Charlene Curtis ’76 and Alex Guerra ’11; Radford Department of Political Science Chair Chapman Rackaway previews Virginia’s 2026 General Assembly for WDBJ-7; and freshman Connor Worthington donates time to a worthy cause in his hometown.

-

Budding sportswriter already has substantial experience covering collegiate sports for a variety of media outlets.

-

Criminal justice student researches police retention

January 16, 2026

“Radford is a fantastic school to do research,” Gary said. “There are so many opportunities here, and you feel very, very, very supported.”