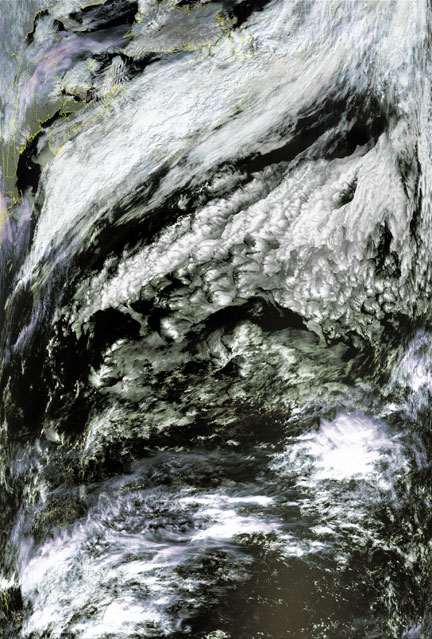

| The image below shows the more extensive image from

which the picture at the far right below was taken. The clouds far out

into the Atlantic Ocean take on almost artistic patterns as the winds

blow them around. This is of course the manifestation of the non-linear

nature of, well, Nature.

|

The early development of "chaos theory" (the popular name for

non-linear phenomena) was advanced greatly by the clouds that

Mitchell Feigenbaum observed in his early years of work at Los Alamos.

From the prologue of the book Chaos: Making a New Science by

James Gleick (http://www.around.com/chaos.html):

"Even Feigenbaum's friends were wondering whether he

was ever going to produce any work of his own. As willing as he was

to do impromptu magic with their questions, he did not seem

interested in devoting his own research to any problem that might

pay off. He thought about turbulence in liquids and gases. He

thought about time--did it glide smoothly forward or hop discretely

like a sequence of cosmic motion-picture frames? He thought about

the eye's ability to see consistent colors and forms in a universe

that physicists knew to be a shifting quantum kaleidoscope. He

thought about clouds, watching them from airplane windows (until, in

1975, his scientific travel privileges were officially suspended on

grounds of overuse) or from the hiking trails above the laboratory.

In the mountain towns of the West, clouds barely resemble the sooty

indeterminate low-flying hazes that fill the Eastern air. At Los

Alamos, in the lee of a great volcanic caldera, the clouds spill

across the sky, in random formation, yes, but also not-random,

standing in uniform spikes or rolling in regularly furrowed patterns

like brain matter. On a stormy afternoon, when the sky shimmers and

trembles with the electricity to come, the clouds stand out from

thirty miles away, filtering the light and reflecting it, until the

whole sky starts to seem like a spectacle staged as a subtle

reproach to physicists. Clouds represented a side of nature that the

mainstream of physics had passed by, a side that was at once fuzzy

and detailed, structured and unpredictable. Feigenbaum thought about

such things, quietly and unproductively. To a physicist, creating

laser fusion was a legitimate problem; puzzling out the spin and

color and flavor of small particles was a legitimate problem; dating

the origin of the universe was a legitimate problem. Understanding

clouds was a problem for a meteorologist. Like other physicists,

Feigenbaum used an understated, tough-guy vocabulary to rate such

problems. Such a thing is obvious, he might say, meaning that a

result could be understood by any skilled physicist after

appropriate contemplation and calculation. Not obvious described

work that commanded respect and Nobel prizes. For the hardest

problems, the problems that would not give way without long looks

into the universe's bowels, physicists reserved words like deep. In

1974, though few of his colleagues knew it, Feigenbaum was working

on a problem that was deep: chaos. "

What would you think if you saw the image below

with Feigenbaum's eyes??

Click

on the image below for a high-resolution (~200k) version.

|

![]()